Copied from the Sid Kipper archive more info

Edited by Chris Sugden and Sid Kipper

The Songs of George Kipper (with accurate words and music), plus his life story, ‘A Mandatory Life’, in 40,000 of his own words.

Published by the Mousehold Press

ISBN no 1 874739 19

CONTENTS:

Awayday

Backwaterside

The Banker’s Daughter

The Belles Of St Just

Big Musgrave

Biker Bill

The Bloody Wars

The Bold Low Way Man

Bored Of The Dance

Cheap Day Return To Hemsby

The Cruel She

Daisies Up

Deadly Dick’s

The Disabled Seaman

Do You Know Ken Peel?

Down, Duvet, Down

The Drag Hunt

East Side Story

Excuse Me

The Farmer’s Crumpet

The Flat Of The Land

Folk Roots ’66

Grey Is The Colour

Haddiscoe Maypole Song

The Happy Clappy Chappy

Hate Story

The Illiterate’s Alphabet

Knapton White Hare

The Lay Of The Lass

Man Of Convictions

The Man With The Big Guitar

My Grandfather’s Cock

Narborough Fair

The Old Lamb Sign

The Outrageous Night

Pretty Penny-Oh

The Punnet Of Strawberries

The Right Wrong Song

The Sisters of Percy

Talking Postman Blues

This Is My Land

The Trousers In Between

The Twenty Pound Frog

Way Down In The Bayeaux Tapestry

We’re Norfolk And Good

The Wide Miss Audrey

Wighton Walnut Song

The Writes Of Man.

the first few decades of

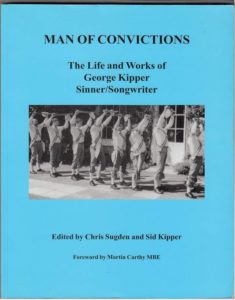

MAN OF CONVICTIONS

(The life and works of George Kipper sinner/songwriter)

Edited by Chris Sugden and Sid Kipper

AN APPRECIATION OF GEORGE KIPPER by MARTIN CARTHY MBE

In every generation there is one outstanding songwriter. George Kipper’s generation consisted of himself and his brother, Henry, so there really wasn’t much competition. Nevertheless, Kipper’s contribution to English song has been remarkable.

He is probably the most unsung singer-song writer of our time. Despite many hundreds of compositions, including the incomparable ‘Biker Bill’, the meretricious ‘Illiterates’ Alphabet’, and the enervating ‘Bored Of The Dance’, he remains to this day almost totally unrecognised. While this may have something to do with his reputation as a master of disguise, it is nevertheless a situation in need of correction.

Consider his seminal 1985 album ‘Live At Her Majesty’s Pleasure’. How is it that this record had so little impact compared to another, similar, product? Was it before its time? Was it a capitalist conspiracy? Or was it that Johnny Cash was actually free to leave San Quentain after his recording to promote the album, while Kipper was not in such a fortunate position?

Consider also the appropriation of many of Kipper’s rights in his own songs by persons close to this very publication.

George Kipper, while serving a great deal of time, has often been ahead of it. For instance, he was making folk songs relevant, by bringing them up to date, three decades before the current trend for it began. It is hardly his fault that the world was not then ready for ‘Dashing Away With The Soldering Iron’. Or that, when the world finally was ready, the song had become somewhat dated. In fact, many of the songs he made relevant then were so successfully of their time that they are now totally irrelevant once more!

Now, at a time when Norfolk suffers from a severe shortage of old folk singers, one of the very best languishes in a prison cell. Of course, this does mean that Kipper now has plenty of time for his song writing. And he has covered the whole gamut; songs to make you think, and songs to stop you thinking; songs to wake you up, and songs to send you into a deep sleep; songs to change the world, and songs to leave it exactly as it was before the song was sung.

It also means, however, that he has been quite unable to protect himself from plagiarism. For instance, some years ago he had high hopes of a song called ‘Narborough Fair’, but those hopes were dashed by the appearance of another, strangely similar, song. Much the same happened with ‘The Streets Of Loddon’, and a wonderful ditty about being lost in the dark at sea, called ‘Have You Got A Light Buoy?’

George Kipper thoroughly deserves to be up amongst the greats. For far too long he has been down amongst the smalls. And he has surely suffered enough. He has served his time, eaten his porridge, and stuffed his bird. Enough is enough. Except in the case of his songs, of course, in which case enough is never sufficient.

So, in closing, I invite you to support the campaign to Free The Trunch One in any way you can. And let he who is without sin cast the first stone. Or she, of course.

Robin Hood’s Bay, 2003

GEORGE KIPPER – A MANDATORY LIFE

Kipper’s the name. George Kipper. George to my mates. Mister Kipper to you. Maybe it’ll be George by the end of the book if you give me a fair hearing and don’t bend the corners of the pages over.

I hate page benders. I’d string them up if I had my way. And I’m talking as someone who’s been a trusty in the prison library for more than fifteen years. But I’ll be coming to that in due course. Before that, I’ll begin.

They say I was born on the day World War One finished, and who am I to argue? November 11th 1918 was a Monday, in case you were wondering. Monday’s child is fair of face, they reckon, but that doesn’t bother me. I don’t have to look at it, do I? Not since I got the beard.

I grew up at Box Cottage. There was my father, Billy, who I always called ‘Father’, and my mother, Sarah, who I always called ‘Sally’. Then she always slapped me on the back of the legs. It was that and the rickets that must have made me a bit bandy. But I wouldn’t notice that if I was you. I’m a bit touchy about it. And don’t say anything where the words ‘passage’ and ‘pig’ come in the same sentence. Even the same paragraph.

Oh yes, I know all about paragraphs. And over the years I’ve learned a lot about sentences. We did all that stuff at school.

I went to the village school. And then I came home again. Lots of times.

THE ILLITERATE’S ALPHABET

(Man of Convictions contains music, as well as lyrics.

However I don’t know how to reproduce it here.)

A is for ‘are’, like ‘are you sixteen?’

Also for ‘aural’, if you see what I mean;

C’s for a ‘cue’, with which pool is played,

and D is for ‘duty’, which we try to evade.

Honour your teacher and see you do well,

Then you’ll be certain you know how to spell.

E is for ‘eye’, it’s open, you see,

F is for ‘F’ – with asterisks, three;

G’s for the gnat that gnaws on a gnu,

and H is for ‘honest’ – would I lie to you?

I’s not for Einstein, or eiderdown either,

J is for ‘Jasmine’, no girl could be blither;

K’s for her ‘knickers’, but not those who take ’em,

and L’s for ‘Llandudno’, if I’m not mistaken.

M’s for ‘Mnemonics’ – with initials so neat,

N’s inconclusive, but not incomplete;

O is for ‘oestrogen’, or so they do tell,

and P’s for ‘phonetics’ which help us to spell.

Q is for ‘quay’, where boats tie along,

but R’s not for writing, unless you’ve writ wrong;

S is for ‘sea’, which laps on the shore,

And T’s for ‘Tsunami’, which does rather more.

U’s for ‘Uranus’, it is, I insist,

V’s for a ‘void’, which we all try to miss;

W’s for ‘why’, but also for who,

and X is for ‘Xerox’, and xylophone too.

Y is for ‘you’, but, then, so is E,

Z’s not for Zar – that’s C or it’s T;

You’ll notice I missed out the one before C;

Well, for present purposes, it’s an absolute B!

SID SAYS: “George writ this song recent, when he found out that loads of people in prison can’t spell proper. Well, it’s not easy. Just take two words – ‘champagne’, and ‘shampoo’. See what I mean? Mind you, when I was a boy that weren’t a problem because we didn’t have either of them. Back then we had real pain and real poo!”

I learned a lot. I learned that whoever invented the 3Rs couldn’t spell. I learned it takes one to know one, that one and two makes a crowd, and it takes two to tangle. I didn’t learn that it takes four to wife-swap till much later, but I did learn that little girls were different to little boys. And that big girls were something else again. I had what they called an elementary education. Then, when I was 14, they chucked me out.

Of course, I was expecting to get chucked out of school. But when I got home that last day to find my bags packed on the doorstep it was quite a shock, I can tell you. Well I am telling you. Father said a few parting words. Through the letter box. He only had a letter box for swank. If anyone had ever written to him he couldn’t have read it, because he was totally illegitimate. He was a bastard, too.

He told me that it was time for me to make my own way in the world. He said he’d heard there were openings for keen, well turned-out lads at the Great Hall. I wondered where they were going to find any of them in St Just-near-Trunch. That’s my village. It’s in Norfolk, if you must know.

It’s not a big place. Not even a ham. Just a hamlet, in the north-east corner of the county. In those days it had two pubs, a school, and a few shops. There was a blacksmith, a cobbler, a joiner and a tailor. Now there’s just one pub and one shop. So much for progress. But there were plenty of ways then for a young man to make an honest living. If he didn’t mind working his way up the hard way. If he didn’t mind hard labour, long hours, and low wages.

I minded all of those. Because life was hard enough in those days. Take my elder brother, Henry. Being elder he got taken on as an apprentice in the family business by Father. Seven years he had to work, without earning a penny. I still can’t see how it takes seven years to learn road sweeping.

So I picked up my bags, and I took myself off to the New Goat Inn. Where I got a job straight away as a pot boy. Not a glamorous job. Every seat in that pub was a commode in those days, and someone had to empty them. That someone was me. But all the while I was planning to move on to bigger things. And I don’t mean a job as a nightsoil man. You hear things in a pub. In my job I smelt things too, but it was what I heard that interested me. What’s what. Who’s who. Where’s when. That sort of thing. And it wasn’t long before I persuaded them to take me along on a night’s poaching.

They didn’t call it poaching, of course. They called it ‘putching’. Because they were good old Norfolk boys, and they didn’t know any worse. So I helped them with their ‘putching’. And they thanked me kindly, and I left empty handed. Another lesson learned. But not the one you might think. Because we all got stopped by the keepers on the way home, and they couldn’t pin anything on me. So they all got three months, and all I got was “We’ll be keeping an eye on you, young Kipper-me-lad”. That and a clip round the ear. But that was standard practice in them days. You expected it. If you’d met a keeper and came away with your ear unclipped, well, you’d feel diminished. Times were hard, but we were harder.

I soon learned that the most successful poachers weren’t the one’s who knew the ways of the wood and the habits of the wildlife. They were the ones who knew the ways of the keepers and the habits of the police. That other stuff is all very well, but a bird in the bush is worth two in the hand when the constabulary want to know what you’ve been up to. Never mind what you’ve read in ‘Tooth And Claw’. ‘The Police Gazette’ is a lot more use.

I hadn’t been working at the Goat long when I got my first business break. This bloke came in who’d got an unexpected surplus of bicycle clips. He was prepared to part with them for the right price. No questions asked. Now, that was a bit tricky. How could I find out the right price without asking questions? You’ve got to have questions if you want answers. On the other hand they reckoned I knew all the answers in those days. So I gave him an answer. He gave me a higher one back, and we met in the middle. With a tanner back for luck.

What he didn’t know was I’d heard something. I’d heard some of them talking about going ratting. Now I was about to introduce them to something. It was the brand new, up to the minute replacement for tying a bit of string round your ankles. I doubled my money overnight.

That money went to the printers. For labels. ‘Kipper’s Patent Compost Starter’, they said. ‘100 per cent natural ingredients’. Well, I could vouch for that. I collected those ingredients in the Goat every night. Very fresh they were, too.

When I tell youngsters that they think I’m taking the pee. Well I wasn’t just taking it, was I? I was taking it, and then selling it on at a profit.

That got me started in business. But it was just the start. Later I sold that business on to Claude Cockle. Of course, when they did the pub up he had to bribe the plumbers. Otherwise he’d have lost his raw material. And let’s face it, you can’t get much rawer than sewage.

There’s another thing I used to hear in the pub. Singing. Proper singing, I mean. What nowadays they call folk singing. And there was money in that too. In fact it’s been a steady earner for me all my life, one way and another.

Back then it was the folk song collectors. Now, I had to be a bit careful with them. Because my family had loads of folk songs, but Father was very strict about not giving them to collectors. Something to do with not wanting to have his dirty bits cut out. But there were songs that had fallen into disuse. Songs that nobody wanted any more. And as long as I handed them over discretely, round the back, there was no harm done. Of course, a lot of those old boys were happy to give away their songs just for a few drinks. But I’ve always reckoned that cash is the sincerest form of flattery.

THE LAY OF THE LASS

As he roved out one November morning,

All searching for a lay;

A maid he heard who sang these words;

“Who’ll whack my diddle, the day?”

So boldly now he stepped up to her,

Without a how-d’you do;

Saying “Now, sweet Miss, if you’ll assist,

I’ll whack your diddle, for you.”

“Stand off”, she said ,”For your intention

Is but to bushwack me;

For you would score my precious store,

And leave me here to grieve”.

Oh, but when she saw his propelling pencil,

Her eyes they opened wide.

Then did she say; “Sir, you must have your way;

Come, whack my diddle”, she cried.

So he took down her dainty crotchets,

Put his finger in her ear;

Then very neat, all on a sheet,

Her parts he entered there.

He had her then between two covers;

Till she gave him her all.

With pencil finished, and no lead in it,

He’d whacked her diddle, withal.

So come all young maids that meet a rover,

Don’t let your bush be whacked.

When in the field keep your lips sealed,

And hold your diddle intact!

SID SAYS; “Some people think folk songs are full of nonsense, what with all their fol-de-rols and fiddle-me-dees. They don’t know what they’re missing. Take this one. It’s what they call a ‘half-entendre‘. It sounds filthy, but it’s actually about collecting folk songs. No nonsense there”.

I unloaded a fair few songs that nobody round our way wanted any more. Stuff like the Haddiscoe Maypole Song. I often wonder what came of some of those old songs. I used to wonder what the collectors wanted them for. Well, I found out soon enough.

HADDISCOE MAYPOLE SONG

Come lasses and laddies, take leave of your daddies,

For Mayday is come, you know;

Come laddies and wenches, take leave of your senses,

Away to the Maypole go.

Now Gary will go with Gail, and Larry will go with Lill;

Harry will go with Hillary Hake, and Barry will go with Bill.

Singing Haddiscoe, thunder rumble-oh,

The wind is up, the sun it hides away-oh;

We must dance the summer in, all in the pouring rain-oh;

For summer is a-coming in, at least they say it may-oh.

For now is your chance to join in the dance,

So take your lover in hand,

For April has gone, but May is come,

And here she sweetly stands.

Now take her in your arms, and if your cards you play,

With any luck you’ll later pluck the darling buds of May.

With your May queen you must go to the green,

To make some mayhem there;

And dance, mayhap, while thunder claps,

And lightning rends the air.

With ribbons gleaming met, and shining iron pole,

Full soon you will feel such a thrill to banish all the cold.

Now our little band is the best in the land,

With drums and pipes, and so

The girls and boys make a wonderful noise,

As they eagerly bang and blow.

Though downpour turn to flood, they never will dismay;

And you’ll hear their cries as the water’s rise,”Mayday! Mayday! Mayday!”

Jump higher and higher until you all tire,

And then jump higher still.

For every Willie shall have his Win,

And every Fanny her Phil.

And though the wind may howl, keep one thought in your head;

You’ll get a kiss, on your chilblained lips, before you go to bed.

Since Adam and Eve every Sally and Steve

Has risen to dance in the May.

So though you moan, and grump and groan,

You’re dancing anyway.

Now jump and jig a jig, although the day be drear,

And then you’ll say, at the end of the day, thank God that’s all over this year.

SID SAYS: “Until George got hold of it there was only a bit of the original song. Then he done a proper restoration job on it, like he used to do with old furniture. It’s just a matter of replacing missing bits, doing some filling, and then adding the wear marks. Only an expert could tell it from the real thing.”

Before long we had people coming into the Goat with these books they’d bought. And in them were all these old songs. But there were gaps where the dirty bits used to be. And these people wanted to collect the dirty bits to stick them in their books. Well, I could help there. And if I didn’t know the exact actual dirty bits for that particular song, well, I could soon get some. How were they to know the dirty bits I sold them came from another song? And if they did notice, that only made them all the more excited. Then they reckoned they’d discovered something. A variant. And those variants, it seemed, were worth even more. Which set me to thinking. If what they wanted was songs that were different to the right ones, well, who was I to deny them?

So I used to sit in my little room, over the snug bar, thinking of dirty bits. I found it helped if I thought of Ruby. She was the Buxton barmaid. I came up with a lot of stuff that way. You’d be surprised how many dirty bits a sixteen year old with time on his hands can come up with. The Cuckoos Nest. That was one of mine. The Banker’s Daughter was another. It was easy. A few lines. A couple of repeats. Some fol-de-rols. And Charlie’s your aunt! Put in a few éds, like ‘walkéd’ and ‘talkéd’, and those collectors couldn’t tell the difference.

I learned quick. I found that the more dirty bits a song had, the better they liked it. That meant they could leave bigger gaps in their books. It saved on the ink. And that meant the people who bought the books had more to fill in. And there I was, only too willing to help them. For a consideration.

THE BANKER’S DAUGHTER

A banker’s fair daughter I once did befriend,

She asked if my assets to her I would lend?

“I’m Penny”, she said, as her locks I admired;

“I could get you a loan if that’s what you required”.

I explained that I needed a place that was right,

To put in my treasure and keep it there tight.

Penny said “You value your goods, I can see;

And I’ll nurture them well if you’ll give them to me”.

“If you come with me, sir, I’m sure I’m not wrong,

I’ll show you the place where your booty belongs”.

She seemed quite alarmed when I entered her closet,

But her interest rose when I made my deposit.

Before very long our transaction was done;

She said “To mix business with pleasure’s my fun”.

“Likewise”, I replied, “I cannot tell you how,

But I’d like to withdraw a little something for now”.

I was sure such a girl would be fully insured,

But in nine months came word that my nest egg had matured.

My holdings had outcomes I could not evade;

My interest had fallen, but the fees must be paid.

Her father insisted that he would not barter;

He wouldn’t be happy till I was a partner.

So look after your pounds, if you would have great wealth,

For Penny, be sure, will look after herself.

SID SAYS: “You get loads of these songs where young men rove out and meet willing young maidens. Well I’ve roved out loads of times, and it’s never happened to me. I reckon I must be roving wrong”.

In a couple of years I’d built up quite a pile of considerations. I kept it under the mattress. It got hard to sleep. Well most of those considerations were in coin.

Now, I’d heard of banks. But none of our family had ever had anything to do with them. It was nothing personal. It was just that we had nothing they wanted. And they weren’t about to give us anything we wanted. But I managed to get my considerations into a wheelbarrow without anyone knowing. And I set off and walked it to Gurnards Bank. That’s in North Walsham.

I had a hell of a job getting the barrow up all those steps and through the revolving doors. But I did it. And then they had the cheek to look down their noses at me. Someone said something about the tradesmen’s entrance being round the back. Well, I soon changed that. Because money talks. And mine said “Look, here’s this young no-nothing with loads of cash”. But they were still suspicious. They wanted to know who I was. Well, I knew that. They wanted to know where I’d got the money from. I knew that too. They asked me lots of questions, but in the end they took the money, and put it in their safe. I got a bank book, and that was that.

Shame I never thought to ask them any questions. Along the lines of “Are you going to get robbed tonight?”.

I read about it a fortnight later. In the North Norfolk News and Agitator. Well, in the pub I only heard very local stuff. So I knew, for instance, that one particular bloke had been in the pub all night when the bank got robbed. Because he told me. Several times. Said he said he wanted me to be clear in case anyone asked.

Next chance I got I went to North Walsham to ask the score. According to the bank it was nil-nil. They hadn’t got my money, and neither had I. They reckoned it was all in the small print. They said my money had to be in the bank for five working days before it was there officially. I’d seen how they worked. At that pace five working days would take them a month. So where was my money in the meantime, I asked. Oh, they said. It was actually in the safe. It just wasn’t officially in the safe. Until the five days were up it was still my responsibility. And to be frank, they said, I’d been pretty irresponsible with it, hadn’t I?

I could have shouted. I could have got violent. I could have refused to leave. But I know when I’ve been done up. I’m a Kipper, after all. So I kept my cool. I turned round and walked out of the bank. And I swore an oath that I’d never go into a bank ever again.

And if I’d stuck to that oath I wouldn’t be where I am now.

George Kipper continues and concludes his story

with words and music for a total of 48 songs in

MAN OF CONVICTIONS

edited by Chris Sugden and Sid Kipper

Published by The Mousehold Press

REVIEWS

Perhaps a future Eurovision entry lurks.”

(Eastern Daily Press)

“Outrageous stuff.”

(The Living Tradition)